Proposal In, Feeling Better

Whew! I managed to get that big telescope proposal in on time. Despite the time crunch and being sick, it was actually a lot of fun putting this thing together. This proposal encompasses a large portion of my dissertation work, and it occurred to me that maybe some of our readers would interested to know what I do for a living.

My project involves the biggest black holes and the biggest galaxies in the universe, and I proposed to look for what appear to be missing giant galaxies. Most galaxies host a central, supermassive black hole. There's one at the center of our own Milky Way, for instance, weighing in at about a million times the mass of the sun. In the nearby universe (a few million light-years away), observations have shown that the sizes of these galactic black holes and their host galaxies are proportional. The bigger the black hole, the bigger the galaxy. Now, the relationship between black holes and host galaxies is key to understanding how galaxies form and grow; it might surprise some of you to know that nobody in astronomy really understands how galaxy formation works. So we've been studying the relationship between supermassive black holes and host galaxies as a function of cosmic time to try to get clues.

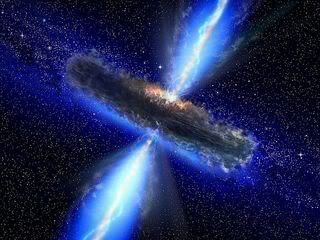

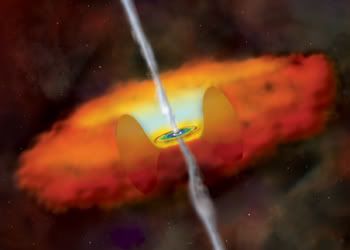

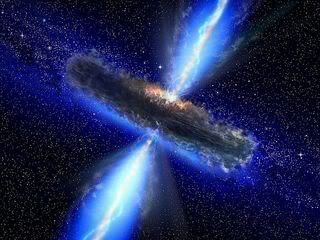

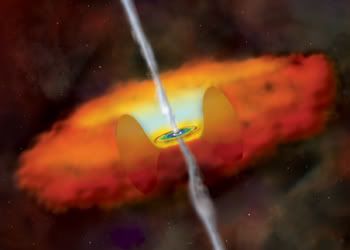

An interior view: these are artists' conceptions of what we think quasars look like. A dusty torus surrounds the black hole and accretion disk, while bipolar jets created by the spinning black hole's twisted magnetic field spew particles at near-light speeds. The torus is a few light-years across.

My previous research used quasars -- very large, very ravenous, black holes thought to reside in the centers of galaxies -- to show that this proportionality between black hole and galaxy sizes was in place as far back as 7 billion years ago, possibly even further. We believe that all galaxies with central, supermassive black holes go through a "quasar phase." This occurs when the black hole feeds on surrounding material that is spiraling down onto the black hole in the form of an accretion disk. The accretion disk material becomes super-heated and shines extremely brightly. So bright, in fact, that the quasar, occupying a region no larger than our solar system, can outshine the entire Milky Way by a factor of 1000. This is handy, because it means that we can study quasars (and hence black holes) from enormous distances. But at some point, the material around the black hole is exhausted and the quasar goes dormant, leaving behind a normal, quiescent galaxy. So the Milky Way, Andromeda, and all the other local galaxies are thought to be quasar relics -- cosmic fossils, if you will.

Andromeda galaxy (M31). Possibly a quasar relic.

I have measured the masses of several distant black holes in quasars, some of which are billions of times the mass of the sun. If we believe the galaxies-as-quasar-fossils idea, then there ought to be some quiet galaxies in the local universe that are proportionally large. The problem is, we don't see any. Not a one so far. So, unless the physics we're using breaks down at some point in cosmic history, this implies a few things: 1) these galaxies exist, but they are rare and we just haven't looked hard enough; 2) these big black holes live in galaxies that are made mostly of dark matter, and are too dim to be observed with current technology; 3) there are gigantic black holes wandering around the universe homeless. Right now I'm proceeding on assumption #1, hence the proposal to look for them with a whopping big telescope. If #1 doesn't pan out, then I proceed with #2 and #3.

Thanks to an endowment from a wealthy industrialist named Alfred P. Sloan, we have a huge project called the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The SDSS has a large telescope in New Mexico whose only job night after night, year after year, has been to map a huge portion of the sky. SDSS has archived spectroscopic and imaging data for millions of astronomical objects, including quasars, galaxies, and stars, and all of it is freely available to anyone in the world who wants it. This was a perfect place to start my search, so I downloaded spectra for six thousand galaxies hoping to find amongst them even just a few galaxies massive enough to host those gigantic far-away black holes. I found six candidates. But I can't claim victory yet. While the SDSS telescope is adequate for a large survey, I need to look at these galaxies with a really honkin' big telescope to get super-high quality measurements. That's what the proposal was for. If I am granted time at the facility I want to use, then I can confirm/deny my initial measurements. If I confirm my measurements, then I will use the Hubble Space Telescope to get high-resolution images to make sure I'm not inadvertently looking at double-galaxies masquerading as singles. Meanwhile, SDSS has taken snapshots of my galaxies so I can quickly inspect them.

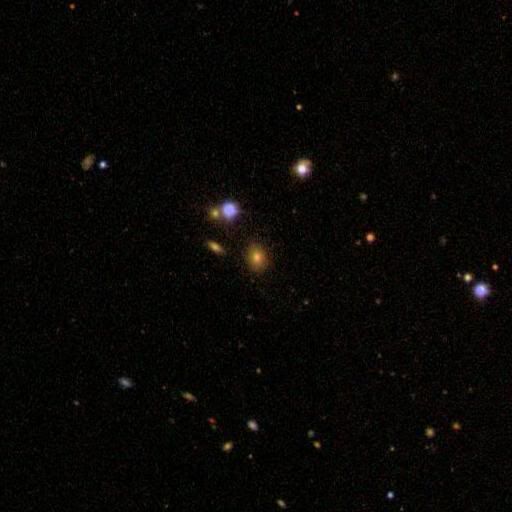

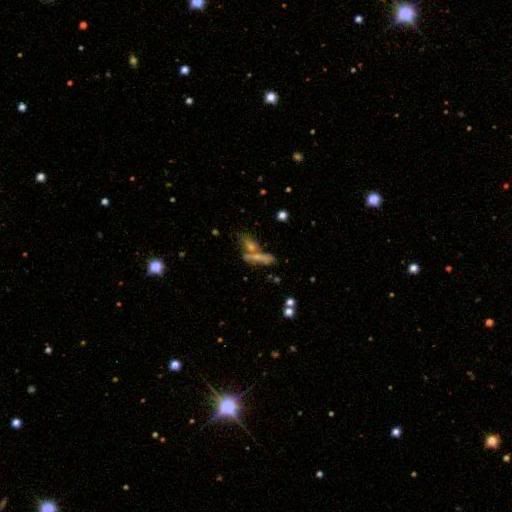

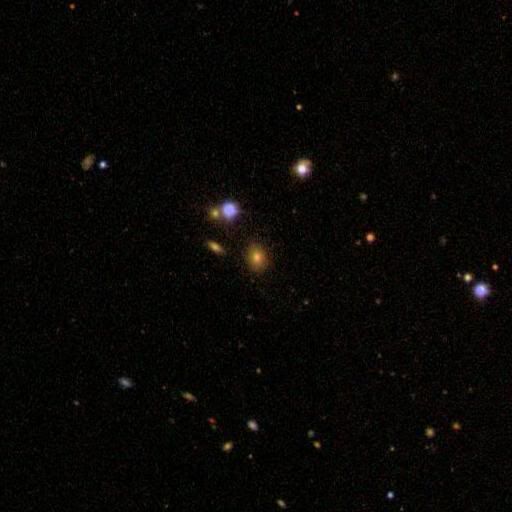

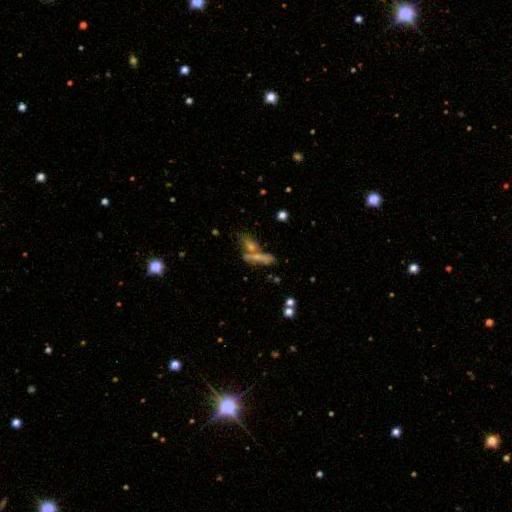

These images aren't nearly as sexy as the ones you've probably seen from Hubble, but keep in mind these were done quickly using a much smaller ground-based telescope -- and these guys are ~3 billion light-years away! The images are ~2 arcminutes on a side, corresponding roughly to 3/100th of a degree on the sky. That's less than one-tenth the apparent size of the moon. When you look at the following images and see how much stuff is contained within this tiny portion of the night sky, reflect on the sheer number of astronomical objects that must be in the entire universe. It's mind-boggling! (For a much more compelling visual perspective, look at the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field image, which encompasses a portion of the sky that's about the same size.)

Anyway. Here's my first galaxy, which is the center blob. This galaxy is in a cluster of galaxies (most are, in fact). That bright blue object to the northwest might be a field star in the Milky Way (field stars in a telescope image are the astronomical equivalent of bugs on a windshield).

And another galaxy, also located in a cluster.

This last one didn't make the cut. When I first measured the mass of the galaxy, it seemed quite large. But when I inspected the image it turns out I was fooled, and you can see why -- it's really two galaxies in the process of merging.

So that's it! Wish me luck with this proposal. If it goes through, I'll get to look at some even more nifty stuff. Meanwhile, I'm starting to get over the bronchitis a little, and will hopefully be posting and commenting more frequently.

My project involves the biggest black holes and the biggest galaxies in the universe, and I proposed to look for what appear to be missing giant galaxies. Most galaxies host a central, supermassive black hole. There's one at the center of our own Milky Way, for instance, weighing in at about a million times the mass of the sun. In the nearby universe (a few million light-years away), observations have shown that the sizes of these galactic black holes and their host galaxies are proportional. The bigger the black hole, the bigger the galaxy. Now, the relationship between black holes and host galaxies is key to understanding how galaxies form and grow; it might surprise some of you to know that nobody in astronomy really understands how galaxy formation works. So we've been studying the relationship between supermassive black holes and host galaxies as a function of cosmic time to try to get clues.

An interior view: these are artists' conceptions of what we think quasars look like. A dusty torus surrounds the black hole and accretion disk, while bipolar jets created by the spinning black hole's twisted magnetic field spew particles at near-light speeds. The torus is a few light-years across.

My previous research used quasars -- very large, very ravenous, black holes thought to reside in the centers of galaxies -- to show that this proportionality between black hole and galaxy sizes was in place as far back as 7 billion years ago, possibly even further. We believe that all galaxies with central, supermassive black holes go through a "quasar phase." This occurs when the black hole feeds on surrounding material that is spiraling down onto the black hole in the form of an accretion disk. The accretion disk material becomes super-heated and shines extremely brightly. So bright, in fact, that the quasar, occupying a region no larger than our solar system, can outshine the entire Milky Way by a factor of 1000. This is handy, because it means that we can study quasars (and hence black holes) from enormous distances. But at some point, the material around the black hole is exhausted and the quasar goes dormant, leaving behind a normal, quiescent galaxy. So the Milky Way, Andromeda, and all the other local galaxies are thought to be quasar relics -- cosmic fossils, if you will.

Andromeda galaxy (M31). Possibly a quasar relic.

I have measured the masses of several distant black holes in quasars, some of which are billions of times the mass of the sun. If we believe the galaxies-as-quasar-fossils idea, then there ought to be some quiet galaxies in the local universe that are proportionally large. The problem is, we don't see any. Not a one so far. So, unless the physics we're using breaks down at some point in cosmic history, this implies a few things: 1) these galaxies exist, but they are rare and we just haven't looked hard enough; 2) these big black holes live in galaxies that are made mostly of dark matter, and are too dim to be observed with current technology; 3) there are gigantic black holes wandering around the universe homeless. Right now I'm proceeding on assumption #1, hence the proposal to look for them with a whopping big telescope. If #1 doesn't pan out, then I proceed with #2 and #3.

Thanks to an endowment from a wealthy industrialist named Alfred P. Sloan, we have a huge project called the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The SDSS has a large telescope in New Mexico whose only job night after night, year after year, has been to map a huge portion of the sky. SDSS has archived spectroscopic and imaging data for millions of astronomical objects, including quasars, galaxies, and stars, and all of it is freely available to anyone in the world who wants it. This was a perfect place to start my search, so I downloaded spectra for six thousand galaxies hoping to find amongst them even just a few galaxies massive enough to host those gigantic far-away black holes. I found six candidates. But I can't claim victory yet. While the SDSS telescope is adequate for a large survey, I need to look at these galaxies with a really honkin' big telescope to get super-high quality measurements. That's what the proposal was for. If I am granted time at the facility I want to use, then I can confirm/deny my initial measurements. If I confirm my measurements, then I will use the Hubble Space Telescope to get high-resolution images to make sure I'm not inadvertently looking at double-galaxies masquerading as singles. Meanwhile, SDSS has taken snapshots of my galaxies so I can quickly inspect them.

These images aren't nearly as sexy as the ones you've probably seen from Hubble, but keep in mind these were done quickly using a much smaller ground-based telescope -- and these guys are ~3 billion light-years away! The images are ~2 arcminutes on a side, corresponding roughly to 3/100th of a degree on the sky. That's less than one-tenth the apparent size of the moon. When you look at the following images and see how much stuff is contained within this tiny portion of the night sky, reflect on the sheer number of astronomical objects that must be in the entire universe. It's mind-boggling! (For a much more compelling visual perspective, look at the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field image, which encompasses a portion of the sky that's about the same size.)

Anyway. Here's my first galaxy, which is the center blob. This galaxy is in a cluster of galaxies (most are, in fact). That bright blue object to the northwest might be a field star in the Milky Way (field stars in a telescope image are the astronomical equivalent of bugs on a windshield).

And another galaxy, also located in a cluster.

This last one didn't make the cut. When I first measured the mass of the galaxy, it seemed quite large. But when I inspected the image it turns out I was fooled, and you can see why -- it's really two galaxies in the process of merging.

So that's it! Wish me luck with this proposal. If it goes through, I'll get to look at some even more nifty stuff. Meanwhile, I'm starting to get over the bronchitis a little, and will hopefully be posting and commenting more frequently.

3 Comments:

Very interesting stuff! You also explain it in terms I can understand. Thanks!!

My pleasure! :) I'm glad you found it readable.

I honestly don't know which scenario is most likely, so I'll try to rule them out one by one.

As for current black hole theory, my project doesn't concern the physical nature of black holes so much as their environments. One thing is certain, however: something is at the centers of these galaxies that is very, very compact and yet exerting a tremendous amount of gravitational force on nearby stuff. Whether the information that crosses the event horizon can ever come back out or not shouldn't affect my study. That said, I could be completely wrong -- and I do have my own ideas about the nature of black holes, which I might post here at a later date. It's pretty wild stuff!

Post a Comment

Testing ...

<< Home